In Part 1, we built a contextual bandit prototype using Python and Mab2Rec. While effective for testing algorithms locally, a monolithic script cannot handle production scale. Real-world recommendation systems require low-latency inference for users and high-throughput training for model updates.

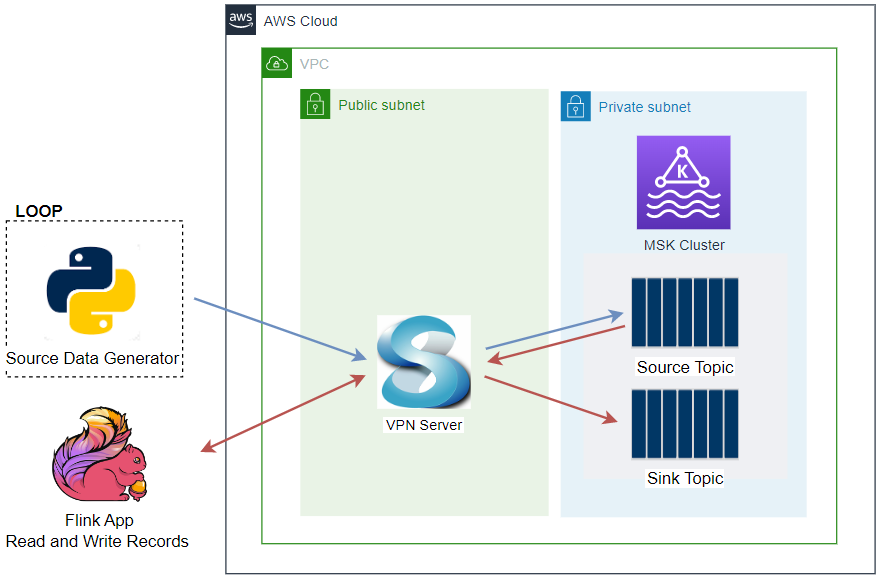

This post demonstrates how to decouple these concerns using an event-driven architecture with Apache Flink, Kafka, and Redis.

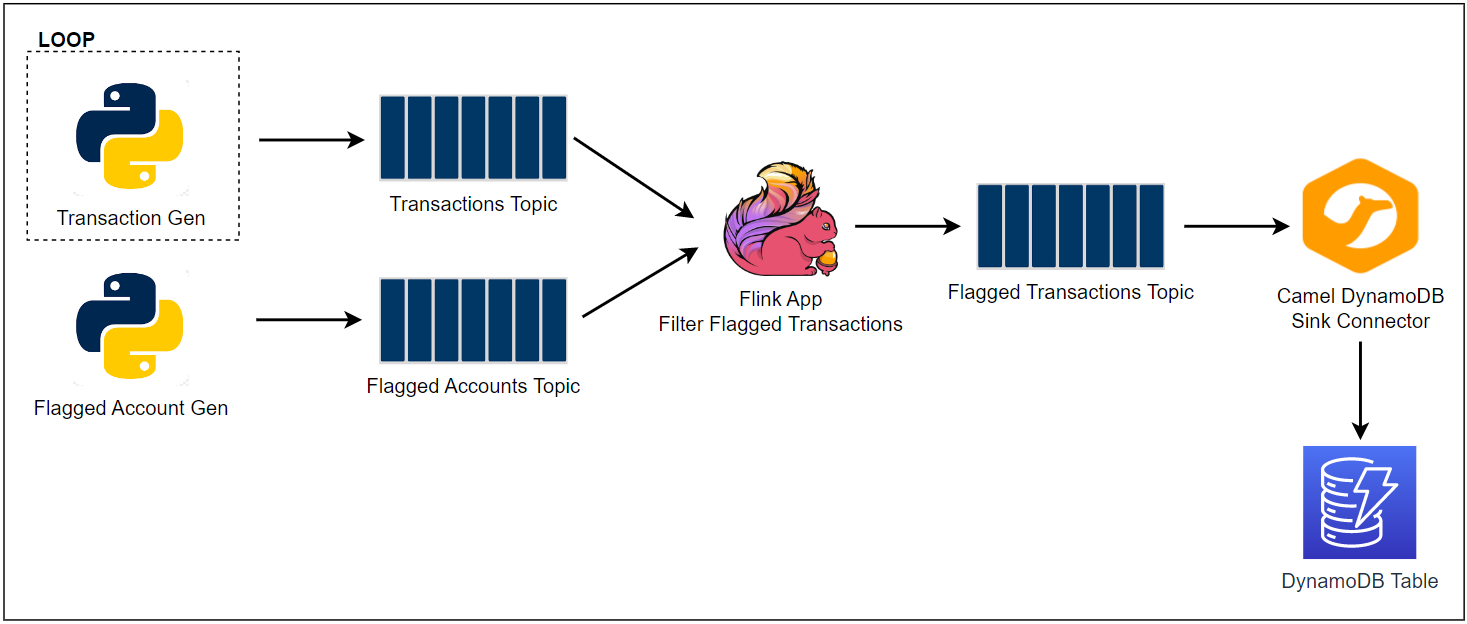

System Architecture

To move from prototype to production, we split the application into two distinct layers: Serving and Training.

- Python Client (Serving): A lightweight, stateless client responsible for inference. It fetches pre-calculated model parameters from Redis, computes scores locally to make product recommendations, and captures user feedback.

- Kafka (Transport): Buffers feedback events asynchronously, decoupling the speed of serving from the speed of training.

- Flink (Training): A stateful streaming application. It consumes feedback events, updates the model parameters (LinUCB matrices $A$ and $b$), and pushes the inverted matrices back to Redis.

- ❗ Unlike Part 1, where training relied on

MABWiser, here it is performed via explicit matrix operations.

- ❗ Unlike Part 1, where training relied on

- Redis (Model Store): Stores the latest model parameters ($A^{-1}$ and $b$) for low-latency access by the client.

📂 Source Code for the Post

The source code for this post is available in the product-recommender folder of the streaming-demos GitHub repository.

Flink Application Design

The Flink job (recsys-trainer) ties these concepts together using a few specific patterns.

Stateful Model Training

The core challenge in distributed online learning is managing state. The LinUCBUpdater function in the Flink trainer acts as the system’s memory. It implements a disjoint LinUCB model, meaning it maintains a completely independent set of matrices for each unique product.

❗The matrices are used to calculate scores for making recommendations.

For each product_id, Flink maintains two pieces of state in RocksDB:

- Matrix $A$ ($d \times d$): Represents the covariance of features seen so far. It tracks Exposure, recording how many times specific user contexts (e.g., “Morning Users” or “Weekend Users”) have been seen for a specific product.

- Vector $b$ ($d \times 1$): Represents the accumulated reward. It tracks Success, recording which features actually led to a click.

The matrix $A$ is initialized as a scaled identity matrix $A_0 = \lambda I$ to ensure invertibility and to encode an initial prior of uniform uncertainty across feature dimensions.

When a feedback event arrives (Context $x$, Reward $r$), Flink performs the updates:

- Update A: $A \leftarrow A + x x^T$. The outer product $x x^T$ increases covariance along the observed feature directions. As similar contexts repeat, $A$ grows in those directions, reflecting increased confidence.

- Update b: $b \leftarrow b + r x$. If the user clicked ($r=1$), we add their feature vector to $b$, reinforcing that preference pattern.

The updated $A$ and $b$ are stored immediately in Flink keyed state (backed by RocksDB). With checkpointing enabled, this state is durably persisted and recovered in case of failure.

Optimization 1: Inversion on Write

To generate a score, we need the inverse matrix $A^{-1}$, which is computationally expensive. If we performed this inversion inside the Python client for every recommendation request, latency would increase significantly. Instead, the Flink training job periodically loads $A$ from state, factorizes it using LU decomposition, computes $A^{-1}$, and stores the inverse in Redis. Because the contextual feature dimension in this demo is small, recomputing the inverse periodically remains efficient while keeping the serving layer lightweight.

Optimization 2: Batched Updates

In a high-traffic environment, a popular product might receive thousands of clicks per second. Inverting the matrix and writing to Redis for every single click would be inefficient.

To solve this, we use Flink timers to buffer updates. The model state ($A$ and $b$) is updated immediately for every event, while the expensive inversion and Redis write are triggered periodically (e.g., every 5 seconds). This drastically reduces CPU load and network traffic while keeping the model fresh.

Scalable Inference Logic

The Python client (eda_recommender.py) is responsible for ranking items. It uses the Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) formula to balance exploiting known good items and exploring uncertain ones.

For a given user context vector $x$ and product $a$, the score is calculated as:

$$ \text{Score}_a = x^T \theta_a + \alpha \sqrt{x^T A_a^{-1} x}, \quad \text{where } \theta_a = A_a^{-1} b_a $$

Prediction ($x^T \theta_a$)

This is the standard Linear Regression prediction. It asks: “Based on historical data, how likely is this user to click?” If the user matches features stored in vector $b$ (features that previously led to clicks), this term is high.

Exploration ($\alpha \sqrt{x^T A_a^{-1} x}$)

- Familiar User: If we have seen this user type many times, the matrix $A$ accumulates repeated contributions of $x x^T$. This increases the magnitude of $A$ in those feature directions. Because the exploration term depends on $x^T A^{-1} x$, a larger $A$ leads to a smaller quadratic form, shrinking the confidence bound. The model therefore relies more on exploitation.

- Cold Start: If we have rarely (or never) observed this feature pattern, $A$ remains close to its initial regularized identity matrix. After inversion, these directions yield larger values of $x^T A^{-1} x$, increasing the confidence bound and encouraging exploration to reduce uncertainty.

- ❗ $\alpha$ is a hyperparameter and it is set to 0.1 as determined in Part 1.

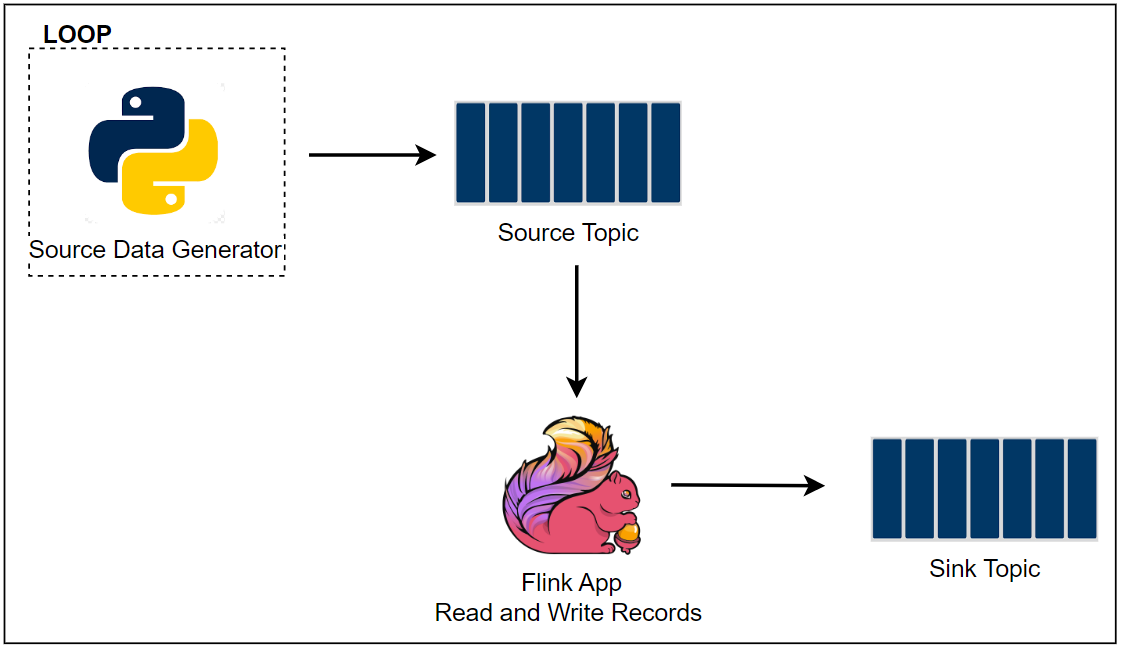

Hybrid Source for Warm Start

Contextual bandits suffer from the “Cold Start” problem. To mitigate this, we implement a Hybrid Source.

- File Source: Reads the historical CSV (

training_log.csv) generated in Part 1 to bootstrap the model state. - Kafka Source: Automatically switches to the live

feedback-eventstopic once the historical data is processed.

Custom Redis Sink

We implement a custom Sink using the Sink V2 API and Jedis. This allows us to perform efficient SET operations to update the model parameters in Redis directly from the Flink stream. Because each update overwrites the full parameter vector, repeated writes remain logically safe under at-least-once delivery semantics. Besides, because the upstream LinUCBUpdater batches the emissions, this sink receives highly aggregated model updates, preventing Redis from being overwhelmed by write operations.

Recommender Simulation Design

To validate the architecture without live user traffic, we designed a Python client (eda_recommender.py) that simulates the entire lifecycle of a recommendation request. This script plays two roles simultaneously: it acts as the Recommendation Service (serving predictions) and the User (providing feedback).

Serving Logic

In a production environment, this logic would live in a high-performance API. For this simulation, the Python client:

- Context Generation: Creates a synthetic user profile (Age, Gender) and derives key temporal features (e.g., Morning, Weekend) from a simulated timestamp to form the full context.

- Model Retrieval: Fetches the latest LinUCB parameters ($A^{-1}$ and $b$) for all active products directly from Redis.

- Scoring and Ranking: Calculates the UCB score for every product, ranks them in descending order, and returns the top 5 highest-scoring items as the recommendation set.

Feedback Generation

To prove the model is learning, the simulation follows the same “Ground Truth” logic used in Part 1:

- Morning Routine: Users click “Drinks & Desserts” (Coffee) between 6 AM and 11 AM.

- Weekend Treats: On Saturdays and Sundays, users prefer “Pizzas” or “Burgers.”

- Price Sensitivity: Users under 25 avoid expensive items.

If any of the recommended top 5 items matches the user’s current context (e.g., showing a Latte on a Tuesday morning), the script generates a Reward (1). Otherwise, it generates no reward (0). This feedback is serialized to Avro and produced to Kafka, completing the loop.

Environment Setup

We use Docker Compose to orchestrate the infrastructure (Kafka, Flink, Redis) and Gradle to build the Kotlin application.

Prerequisites

Clone the repository and infrastructure utilities, then download the required connectors (Kafka, Flink, Avro).

1git clone https://github.com/jaehyeon-kim/streaming-demos.git

2cd streaming-demos

3

4# Clone Factor House Local for infrastructure definitions

5git clone https://github.com/factorhouse/factorhouse-local.git

6

7# Download Kafka/Flink Dependencies

8./factorhouse-local/resources/setup-env.sh

9

10cd product-recommender

Build and Launch

We bootstrap the environment by generating training data, building the Flink JAR, and launching the cluster. We use Kpow and Flex to monitor the Kafka and Flink clusters; these tools require a Factor House community license. Visit the Factor House License Portal to generate your license, save the details in a file (e.g., license.env), and export the associated environment variables (KPOW_LICENSE and FLEX_LICENSE).

With the license configured, launch the Docker Compose services as shown below.

❗ You do not need Kotlin or Gradle installed locally. The ./gradlew script handles all build dependencies.

1# Setup Python and Generate Bootstrap Data

2python3 -m venv venv

3source venv/bin/activate

4pip install -r requirements.txt

5python recsys-engine/prepare_data.py

6

7# Build Flink Application (Shadow Jar)

8cd recsys-trainer

9./gradlew shadowJar

10cd ..

11

12# Launch Infrastructure (Kafka, Flink, Redis, Kpow)

13export KPOW_SUFFIX="-ce"

14export FLEX_SUFFIX="-ce"

15export KPOW_LICENSE=<path-to-license-file>

16export FLEX_LICENSE=<path-to-license-file>

17

18docker compose -p kpow -f ../factorhouse-local/compose-kpow.yml up -d \

19 && docker compose -p stripped -f ./compose-stripped.yml up -d \

20 && docker compose -p flex -f ./compose-flex.yml up -d

Live Recommender Simulation

Once the infrastructure is running, Flink will first process the historical events to warm up. Once the historical processing is complete, we can run the Python client to simulate live traffic.

To visualize the system in action, open two terminals.

Terminal 1: Client

Run the Python script. It acts as the user, receiving recommendations and sending feedback (clicks) to Kafka.

1python recsys-engine/eda_recommender.py

Terminal 2: Trainer

Watch the Flink TaskManager logs. You will see the application reacting to the events sent to the feedback-events topic in real-time.

1docker logs taskmanager -f

Result

You will see a series of feedback events generated by users on the left-hand side. On the right-hand side, you can see the logs confirming that model parameters are being sent to Redis in batches.

This confirms the closed loop: Read (Redis) -> Act (Kafka) -> Learn (Flink) -> Write (Redis).

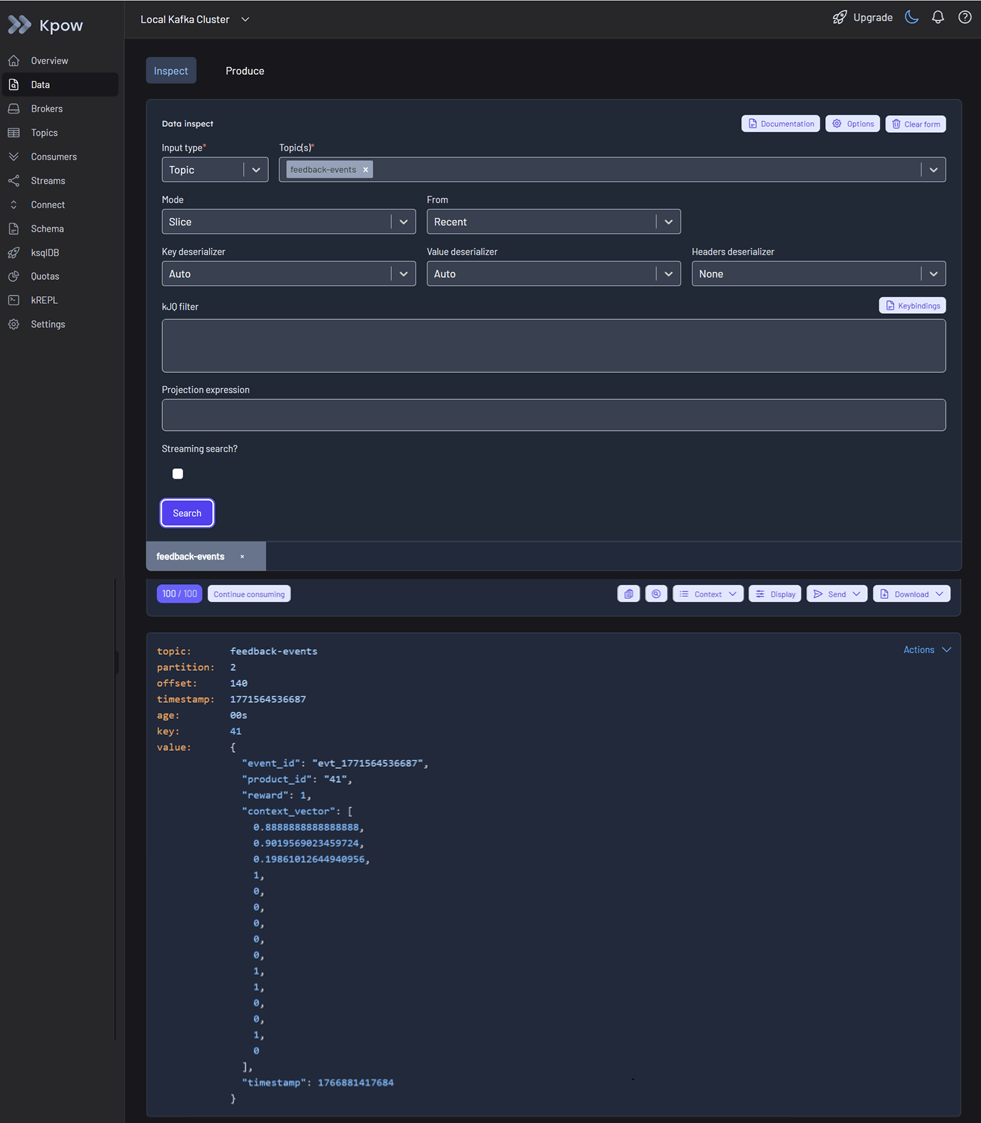

You can inspect feedback events on Kpow at http://localhost:3000.

Teardown

To stop the cluster and remove resources:

1docker compose -p flex -f ./compose-flex.yml down \

2 && docker compose -p stripped -f ./compose-stripped.yml down \

3 && docker compose -p kpow -f ../factorhouse-local/compose-kpow.yml down

Conclusion

Traditional recommendation systems such as Collaborative Filtering rely on long-term interaction history and often treat user preferences as static. As a result, they struggle to incorporate immediate context, missing situational shifts like a user preferring coffee in the morning but pizza in the evening.

To overcome this, we use Contextual Multi-Armed Bandits (CMAB), an online learning approach that balances exploitation and exploration using real-time contextual signals. While our Python prototype in Part 1 validated the concept, it was not built for scale.

We then evolved it into a production-ready event-driven architecture: Kafka streams feedback events, Flink handles distributed stateful training, and Redis serves precomputed parameters for low-latency inference. This design enables horizontal scalability and real-time adaptation to user behavior.

Comments